The Mental Health Act

Understanding & exercising your rights

Iva Cheung and Maja Kolar

April 11, 2022 • 9 Min Read

Understanding the Mental Health Act

Content note: This article uses the term “mental disorder” because that’s the legal term used in the Mental Health Act. It’s not linked to any specific psychiatric diagnosis and is not the same thing as “mental illness.” We acknowledge that this term can mean different things to different people and that some people might find it stigmatizing.

Being diagnosed with a mental health condition doesn’t mean you will necessarily be hospitalized. Most people can get treatment and support in the community through counsellors or other providers, like the ones listed on MindMapBC. But some people might end up hospitalized under the Mental Health Act.

The Mental Health Act is a provincial law that gives doctors the ability to hospitalize people experiencing mental health issues in order to give them psychiatric treatment against their will.

Some people who experience a mental health issue might not recognize that they’re unwell or that they might benefit from psychiatric treatment, so they decline or avoid treatment. The aim of the Mental Health Act is to allow people in these situations to get the treatment they need.[Guide 2005, 1] But some people have expressed concerns that the Mental Health Act could be used to control people’s behaviours and actions.[Boyd & Kerr 2015]

Being involuntarily hospitalized (that is, without consent) under the Mental Health Act, sometimes called being “certified,” can be scary for many people. Involuntary patients may find their hospitalization experience confusing, stigmatizing, or traumatizing.[RCY 2021, p. 45]

This article covers how you can plan ahead so that, if you (or someone you care about) are ever involuntarily hospitalized, you know how to exercise your rights.

Voluntary versus involuntary psychiatric treatment

If you do need hospital care and are willing to accept it, you should be able to get it voluntarily. If you're in the hospital as a voluntary patient, you have the right to (a) refuse treatment and (b) leave whenever you want. You also have the right to know if you're a voluntary or involuntary patient.

In BC, you can be admitted as an involuntary patient under the Mental Health Act only if a doctor has examined you and believes that you meet all four of these criteria:

- you have a mental disorder* that seriously impairs your ability to react appropriately to your environment or to other people;

- that mental disorder* needs to be treated;

- you must be hospitalized to prevent you from substantially deteriorating mentally or physically or to protect you or others; and

- you aren’t suitable to be a voluntary patient.

The average length of an involuntary admission is 14 days. [BC Office of the Ombudsperson, 2019, 16]

*Content note: This article uses the term “mental disorder” because that’s the legal term used in the Mental Health Act. It’s not linked to any specific psychiatric diagnosis and is not the same thing as “mental illness.” We acknowledge that this term can mean different things to different people and that some people might find it stigmatizing.

Your rights as an involuntary patient

If you’re hospitalized as an involuntary patient, you can’t leave the hospital without the doctor’s permission, and you will be given treatment even if you don’t agree with it. But you still have rights.

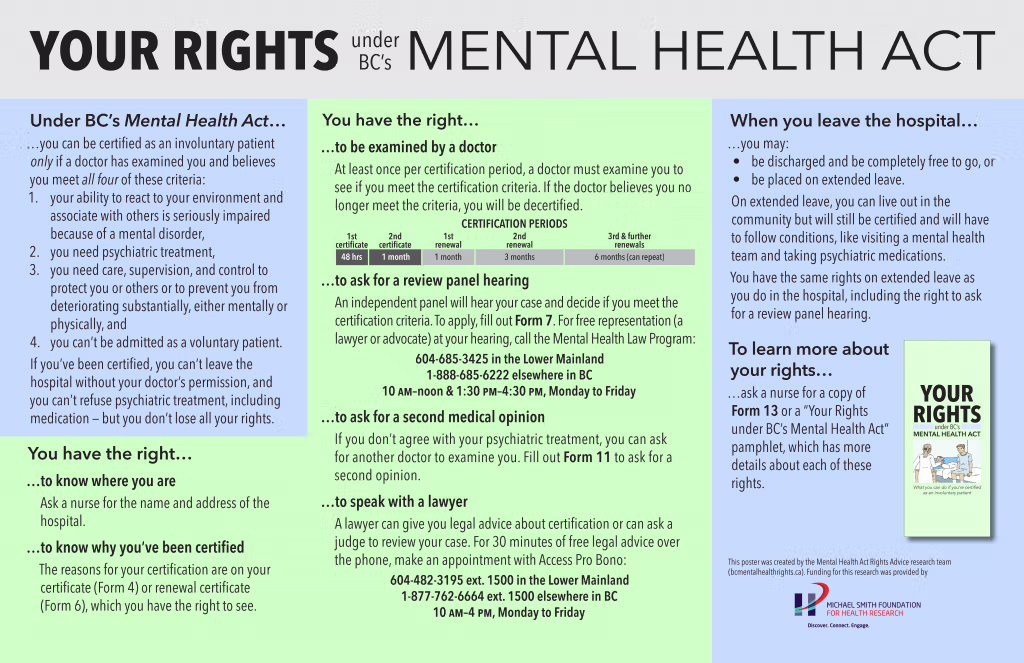

Your treatment team must give you information about your rights when you’re admitted, using a document called Form 13. Some people find the document hard to understand, so a team of SFU researchers and patient partners created a set of information materials to help involuntary patients better understand their rights.

At BC Mental Health Rights, you can find a pamphlet, a wallet card, posters, and a video that explains what your rights are. The information is available in nine languages.

Additional resources available at www.bcmentalhealthrights.ca/

Near relatives

If you’re hospitalized as an involuntary patient, your treatment team will ask you to nominate someone to be your near relative. This could be a family care partner or a close friend—they don’t have to be related to you by blood or marriage. The treatment team will tell your near relative that you have been involuntarily hospitalized and give them information about your rights.

If you’re worried about becoming hospitalized, ask someone close to you if they would be willing to be your near relative. If they agree, it’s a good idea to have their name and contact information handy (you can record it on the Your Rights under BC’s Mental Health Act wallet card, for example) to give to your treatment team.

Review panel hearings

Involuntary patients who are hospitalized for more than 48 hours have the right to challenge their involuntary status by applying for a hearing with a review panel, which is independent of the hospital. The review panel hears evidence from you and from the hospital and decides if you should be discharged.

You're allowed to have a representative at the review panel hearing to help you argue your case. This representative could be a lawyer or legal advocate through the Mental Health Law Program, a lawyer you hire for yourself, or a friend or family member. You can also call witnesses to support your case.

If you think you might apply for a review panel hearing if you become hospitalized as an involuntary patient, think about who you might want to represent you at a hearing or support you in other ways, like being a witness for you.

For more information on review panel hearings, including how to apply, visit the BC Mental Health Review Board site.

Second medical opinions

Involuntary patients who are hospitalized for more than 48 hours have the right to challenge their treatment plan by asking for a second medical opinion from a doctor who is not on their treatment team. This doctor can be anyone licensed to practice medicine in the province.

If you ask for a second medical opinion, the doctor you choose will examine you, review your treatment plan, and make recommendations. Your hospital treatment team must consider these recommendations but isn’t required to follow them.

If you’re worried about becoming hospitalized, think about what doctor you might ask to give a second medical opinion. If you have an existing relationship with a doctor in the community who knows your health history, this doctor might be a good choice. Have their name and contact information on hand.

You, or someone on your behalf, can apply for a second medical opinion by filling out Form 11 and giving it to the treatment team.

Advice from a lawyer

Involuntary patients have the right to contact a lawyer, who can:

- give them advice about their rights; and

- represent patients who want to challenge their involuntary status, either at a review panel hearing or in court.

Legal and court fees can be expensive, so many people don’t have access to a lawyer. But if you already have a lawyer, keep their name and contact information with you, because they could help you if you become hospitalized under the Mental Health Act. There is also the option of getting 30 minutes of free legal advice if you don’t have a lawyer. For more information on your right to contact a lawyer, see the rights materials at BC Mental Health Rights, as well as Health Justice’s Getting Legal Help: Legal and Complaint Resources for People Impacted by the Mental Health Act.

Advance care plans

One way to empower yourself is to make an advance care plan and write down your wishes for your treatment if you're hospitalized under the Mental Health Act. These kinds of plans are most helpful if you make them with family care partners and community mental health supports. [Nicaise et al. 2013]

Be warned that advance care plans are not legally binding under BC’s Mental Health Act. So you might still get care that you don’t want even if you’ve made a plan. That said, many people find the process of making an advance care plan therapeutic because it helps engage them in their own recovery. [Khazaal et al. 2014]

In your plan, you can write down what kinds of treatments you would prefer and which ones you want to avoid. For example, if you had a bad reaction to a certain medication, describe this reaction in your plan. You can also explain what strategies have helped you through a crisis in the past and what kinds of approaches might trigger a traumatic reaction for you.

Once you’ve made a plan, give a copy of it to someone you trust, like the person you would want to be your near relative (see above). This person can give this information to the hospital if you ever become involuntarily hospitalized.

To learn more or get help

- A Path Forward: Human rights-based guiding principles for BC’s mental health law and services: https://www.healthjustice.ca/guiding-principles

- BC Mental Health Rights: https://www.bcmentalhealthrights.ca/

- Health Justice: https://www.healthjustice.ca

- Access Pro Bono Mental Health Program (for 30 minutes of legal advice): https://www.accessprobono.ca/our-programs/mental-health-program

- Community Legal Assistance Society Mental Health Law Program (for representation at review panel hearings): https://clasbc.net/get-legal-help/mental-health-law/

- BC Mental Health Review Board: https://www.bcmhrb.ca

- Advance care planning: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/seniors/health-safety/advance-care-planning

About the Authors

Iva Cheung (she/her), PhD, is a Certified Professional Editor and health communication researcher who has studied how to help people involuntarily hospitalized under the Mental Health Act better understand their rights. She specializes in working directly with people with lived experience to create accessible health information in plain language, including the materials at BC Mental Health Rights.

Maja Kolar (pronouns: they/ them/ theirs) is the first graduate of the UBC School of Nursing’s Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) program who is a registered psychiatric nurse. They are currently working as an Advanced Practice Nurse with a focus on the Mental Health Act, and are also an Adjunct Professor at UBC's School of Nursing. Their research focuses on exposing health and social inequity for people experiencing mental health issues.

References

- BC Office of the Ombudsperson (2019). Committed to change: Protecting the rights of involuntary patients under the Mental Health Act, https://bcombudsperson.ca/assets/media/OMB-Committed-to-Change-FINAL-web.pdf

- Boyd, J., & Kerr, T. (2016). Policing ‘Vancouver’s mental health crisis’: a critical discourse analysis. Critical Public Health, 26(4), 418-433.

- Khazaal, Y., Manghi, R., Delahaye, M., Machado, A., Penzenstadler, L., & Molodynski, A. (2014). Psychiatric advance directives, a possible way to overcome coercion and promote empowerment. Frontiers in public health, 2, 37.

- Ministry of Health (2005) Guide to the Mental Health Act, https://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2005/MentalHealthGuide.pdf

- Nicaise, P., Lorant, V., & Dubois, V. (2013). Psychiatric advance directives as a complex and multistage intervention: a realist systematic review. Health & social care in the community, 21(1), 1-14.

- Representative for Children and Youth (2021). Detained: Rights of children and youth under the Mental Health Act, https://rcybc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/RCY_Detained-Jan2021.FINAL_.pdf

Next Article →

Know Your Rights